Last month, we looked at the issue of ‘Conversion Stress’ and how you can overcome this to unearth opportunities in your target area. This relates to policy imposed by the local planning authority to control the number of single dwellinghouses in a street that would be allowed to convert to smaller units – either as HMOs or as flats.

In this month’s article, we look at how the issues looked at last month were applied to a recent case in the London Borough of Lambeth, where we successfully obtained planning permission to extend and split an existing family dwelling into 3no separate flats.

The Property

We were instructed to seek permission for the conversion of and extensions to a 4-bedroom property in a terraced street in the London Borough of Lambeth. The initial proposals sought to provide 4 flats – 1 x 3-bedroom 6-person, 2 x 2-bedroom 4-person and 1 x 1-bedroom 2-person.

The property is not listed but is in a Conservation Area and in a street under ‘conversion stress’.

Clarifying the Conversion Stress Policy (CSP)

Lambeth’s existing Local Plan policy relating to properties caught by a CSP was not very clear. It was poorly drafted and provided no clear certainty in any given situation for a developer to know whether or not they would fall outside the policy.

The existing policy had, for instance, no minimum size threshold such as one might say that if, for example, the property is more than 150 sqm in size then the Council would accept conversion in principle. In addition, it did not clearly state whether one had to re-provide a family dwelling within the converted building.

However, we were assisted by the emergence of a new, draft version of the same policy in the draft Local Plan. This policy made the position much clearer, at least on size thresholds. We knew that as the property was over the 150 sqm threshold for conversion set by this policy then it would be likely to be acceptable in principle.

In any event, just to be sure that our own application would be consistent with how officers might read the policy, we contacted a Policy Officer by email first. I was fortunate enough to speak to the officer over the telephone (no mean feat these days!) to confirm their understanding of how the policy might work in respect of this property. This proved to be extremely useful – as you will see below.

The importance of family dwellings

A feature of this policy was that, as far as practicable, we had to try to retain a three-bedroom family dwelling within the conversion scheme.

This is highly common amongst local authorities, who are often concerned about losing larger family homes from local housing stock, where there is a present need for such stock.

However, it is not the same in every case. Some local authorities place the bar even higher; for instance, the London Borough of Newham will only accept a conversion of a large family home in a suburban road if the separate flats are each at least 4-bedrooms. On the other hand, the London Borough of Barnet, has no specific policy requirement and will sometimes allow only smaller flats even in suburban streets (they take a slightly different approach where the size of development is large enough to provide at least some 3-bedroom flats).

In addition, if the site is in a town centre area, then the premium for external garden space and general high-density environment is often readily accepted as not appropriate for 3-bedroom flats, hence 1-bedroom and 2-bedroom apartments are more likely.

Initial officer resistance

Officers do not always read the information in front of them properly – and this was a case in point! After having checked with the policy officer that we were within the conversion stress policy, we set this out very clearly to the case officer, only to receive a short email back stating that she would recommend the application for refusal because the proposal did not comply with their conversion stress policies.

This confusion and the ‘left hand not knowing what the right hand’ is doing or saying is common-place in the planning system, unfortunately.

It is for this reason, knowing the importance of the conversion stress policy to officers, that we laid out the groundwork first by contacting a Policy officer and confirming our approach with them in writing before making the application. This gave us the ammunition needed to bypass the case officer and go to their team leader to ask for a review of their initial recommendation.

During the Pandemic (and probably for some time to come), home and remote working has weakened the strength of senior officer supervision and thus you will need to be prepared for officers in some cases ‘going off on a frolic of their own’.

I’m pleased to say that this review worked and the junior officer was promptly overruled. In fact, she was replaced by a more senior officer, who was a lot more experienced, more reasonable and more responsive.

Design changes

The position of the property in a Conservation Area meant that the officers took an especially keen interest in any proposed extensions or infilling to the property, both on an individual and cumulative basis in terms of its impact on the character of the property as a whole.

The officers sought to distinguish this case from other examples in the road where significant extensions had been undertaken. They will often do so by either noting that such extensions: (1) do not have planning permission, (2) might be lawful but the planning merits were never tested under a planning permission so went undetected for four or more years, or (3) they were granted permission but under older Local Plan policies.

The front and rear elevations and Sections (BB) below in comparison show where the principal changes had to be made to the scheme.

In this month’s article, we look at how the issues looked at last month were applied to a recent case in the London Borough of Lambeth, where we successfully obtained planning permission to extend and split an existing family dwelling into 3no separate flats.

The Property

We were instructed to seek permission for the conversion of and extensions to a 4-bedroom property in a terraced street in the London Borough of Lambeth. The initial proposals sought to provide 4 flats – 1 x 3-bedroom 6-person, 2 x 2-bedroom 4-person and 1 x 1-bedroom 2-person.

The key aspects discussed and resolved with the design officers were as follows:

- Second floor rear extension height was lowered to reduce bulk.

- Small fan light added above the second floor rear extension to match similar feature to other houses in the same group.

- Third floor rear extension removed.

The following CGI shows the proposed changes to the rear elevation (application property on the right) in context with neighbours.

We were able to agree the retention of most other changes to the property, including at ground floor level. However, the loss of the third floor extension and reduction in rear second floor height meant that the scheme was now a 3-unit conversion, instead of four.

However, as the London Borough of Lambeth also usually seek a financial contribution toward affordable housing on ‘small sites’, we were able to ‘leverage’ the loss of the fourth unit and reduction in GDV to successfully argue that the scheme could not viably provide a financial contribution.

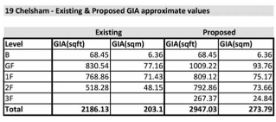

As can be seen from the above table, the scheme added just under 71 sqm to the original floor space (the equivalent of a new 3-bedroom flat); an increase of nearly 35% on the size of the property. So overall, still a good result!

Car-free and car-capped housing

In common with many local authorities, car parking for the new units was actively discouraged by the Council. We were though allowed to retain the current on-street parking permit for the family dwelling. Therefore, the scheme was ‘car-capped’ rather than completely car-free.

The Council instead wanted to see a more open forecourt with some soft landscaping, and bin stores. The bicycle stores would be positioned to the rear via the side passage.

Conclusion

Each local authority will have its own housing pressures and priorities. You may find that in some cases there is no conversion stress policy or requirement for a minimum dwelling mix with family-sized units. However, if in any doubt and such a policy exists, then it is vital that the scheme is properly tested at the earliest possible stage against such policies, to see if there is a possible conversion development in the first place. Once the principle of conversion has been established, then most local authorities will accommodate design changes to the scheme without the need for a pre-application and the opportunity for ‘planning gain’ through conversion opens up.